Welcome!

Thank you for your continued support and interest in my work. Due to many requests and massive pressure on my time, I have set up a Q&A below. These are based on the valuable questions that I receive via email and on social media.

I wish you all the best in your pursuits.

Thomas

What was the main reason for making the switch from marine biology to photojournalism?

Photography has been a passion for as long as I can remember, but I studied marine biology. My goal was tocontribute to ocean conservation through scientific research. My work as a field biologist gave me a global perspective on conservation ranging from the coral reefs of northern Mozambique to the seagrass beds of Central America. As a graduate student I researched the impacts of South African abalone poaching, fueled by the demand from international crime syndicates. I discovered that the scientific data on decimated abalone populations were not influencing protection measures. However, the photographs I took (images of poaching and barren seascapes) incited a much more visceral and immediate response from the public. Irealized that I could help further conservation efforts more through my photographs than through statistics. So, I left behind a fledgling scientific career for the nomadic life of a photojournalist.

What preparation goes into “getting the shot”?

For every day in the field I spend at least 7 days behind the computer, on the phone, writing emails, packing, or organizing travel logistics. For every assignment I read hundreds of scientific reports and research papers. I spend ours on the phone or skype talking to people who are experts in the subject I am shooting.

A big part of my preparation comes in knowing what already exists. The key to great photography is to be original and it helps to have an encyclopedic knowledge of what has come before. Otherwise you are likely to think you have just blazed a new path, when it is really just a well worn path. You have to build a "photographic library" in your head to inform the creation of new photographs.

I also visualize many of the images I want to take. There are endless lists in my notebooks and several rough sketches. By the time I have checked in for my flight, I generally have mapped out exactly what photographs I want and how I will take them. Some of this might sound clinical, but this structure gives me confidence and peace of mind, which opens the window for creative freedom.

When did the passion for the ocean and underwater photography begin?

My love affair with the ocean began the moment I put my head under the water. I started snorkeling at the age of six and began diving at twelve. At the same time I immersed myself in the work of Jacques Cousteau and the early underwater stories by David Doubilet in National Geographic Magazine. The ocean was this irresistible lure that would not go away. I wanted to experience what I saw on TV and in magazines. I took my first underwater photographs at age 12 with a bright yellow Minolta Weathermatic. When I was 16 my parents gave me a Nikonos V for my birthday and it changed my life.

Why are sharks a major focus of your work?

The articles and films that I remember most vividly from my childhood were those featuring sharks. These large ocean predators served as a gateway for me. Sharks were my first photographic subjects. Living along the South African coast allowed me direct access to the realm of the most reviled and misunderstood shark, the great white. Rather than adding to the growing stock of menacing, toothy white shark photographs, I wanted to capture the more serene nature and prehistoric perfection of these creatures. I also became aware of the darker side of our relationship with sharks when, for example a shark with its fins cut off washed up in a bay near my house, and teeth from protected white sharks appeared in a local curio shop. Increasingly, I realized I wanted to go beyond creating beautiful images and capture as complete a story as possible through conservation photojournalism.

Why is photography important for conservation?

The legendary conservationist George Schaller wrote, “Pen and camera are weapons against oblivion, they can create awareness for that which may soon be lost forever.” Schaller’s words are my mantra and inspire me to keep working for change. Photographs, I believe, are one of the most powerful weapons in the marine conservation arsenal, and it has become my life’s work to create images that inspire people to act. I spend upward of 250 days a year shooting all over the world. For half of that time I visit beautiful places and take photographs that celebrate the ocean. I commit the other half to documenting the effects of our growing demand on the sea. I take a “carrot-and-stick” approach to conservation photojournalism. I walk a fine line of creating imagery that both disturb and inspire. My aim is to tell balanced and honest stories that encourage people to revel in the beauty of the ocean, but also to understand how we affect its health. I am a Senior Fellow and board member of the International League of Conservation Photographers, a collective of some of the best wildlife and environmental photographers who tackle some of world's most important conservation issues. The greatest conservation victories occur when photographers, scientists and NGOs collaborate.

How can people most effectively support conservation efforts to protect marine life?

Many people feel that they don’t have the power to make a difference in marine conservation. Nothing could be further from the truth. Many of fish we regularly eat, like some species of tuna come from fisheries that catch and kill a large number of sharks. Eating shrimp or prawns is often connected to questionable fishing methods and turtle bycatch. The first step is to educate yourself and become more intentional about the kind of fish you order at a restaurant or put on your dinner table. Ask questions, think, be selective and vote with your wallet. It’s difficult to turn down certain seafood dishes, especially if it is a habit (or delicious). But as a consumer you have massive power to change the way markets and restaurants do business and make it ripple all the way up the supply chain and straight back to the fishermen. In addition, educate yourself about marine conservation organizations near you and see how you can get involved. You don't have to be a marine biologist (or a photographer for that matter) to be an ocean guardian. Here is a good starting point: List of marine conservation organizations

Which methods do you use?

On most assignments I take most of my underwater photographs while free diving. The two critical factors in getting great images are TIME and PROXIMITY. Free diving allows me to spend up to eight hours in the ocean without the disturbing bubbles and vibrations of SCUBA. The only way to shoot powerful imagery underwater is to get close and most of my work is wide angle where my subject is less than half a meter away. I have to gain my subject’s trust and find ways for it to allow me to enter its personal space without minimal disturbance. I find this very difficult to do on a short scuba dive with cumbersome equipment.

How are conservation messages best conveyed?

You can do conservation photography in two ways. One way is to show people the beauty and the biodiversity that remains. You can say, ‘this is what is at stake and what we still have to protect.’ To do this you have to create a character around the animal by describing behavior that endear themselves to the audience. It’s about nurturing a connection between the audience and the species. The risk with this approach is that you can create the impression that everything is okay, which makes people complacent. The other approach focuses on the problem. The truth is that the oases of biodiversity in wildlife documentaries are a tiny fraction of our planet. They are a splice in time. The reality is that our exploitation of the planet is minimizing our chances for long term success as a species. We’re at a point where our actions have shaped the planet as much as geological processes. This is not something people want to face and they try to avoid images that remind them of this. It’s a challenge, but just because they’re hard to look at does not mean these photographs cannot be beautiful. As a conservation photographer, I had to learn to create engaging imagery on the darker side of things. I am constantly trying to finding a balance between the carrot and the stick.

To the general public, conservation can be a pain, because it equates with short-term compromise, change and sacrifice. Whether it’s boycotting a certain fish from your plate, writing a letter to your congressman or driving your car less, it’s inconvenient. You are only going to change your lifestyle if you’re convinced and sufficiently motivated. Conservation photography is a means of providing proof and motivation.

What advice do you have for budding conservation photographers?

To be successful as a conservation photographer, you have to be obsessed with creating images and telling stories that matter. It’s also essential to try to make original and memorable photographs. My editor at National Geographic Magazine, Kathy Moran, challenges me to do one of two things: show her something that the world has never seen before or show her something familiar from a completely unfamiliar perspective. Conservation photography can be an emotional roller coaster. It can be socially isolating, logistically exhausting, and physically demanding. It is also the most emotionally and professionally rewarding pursuit that I can imagine.

In the magazine world, media production budgets are shrinking. It’s becoming harder to tell stories with real conservation value. I think we’re losing a lot of great young photographers to other careers, which are perhaps more reliable. To survive and thrive in this profession you have to be a hopeless optimist, believing that the next great picture is just around the corner. It’s not just the photography. It’s the drive. It’s the commitment. It’s the obsession with the subject. You have to be somewhat insane to make it in this game. That’s the reality. You have to want it so badly and you have to be in love with the process, with the research and with the science. You have to be hungry.

What was your most memorable shoot? Why?

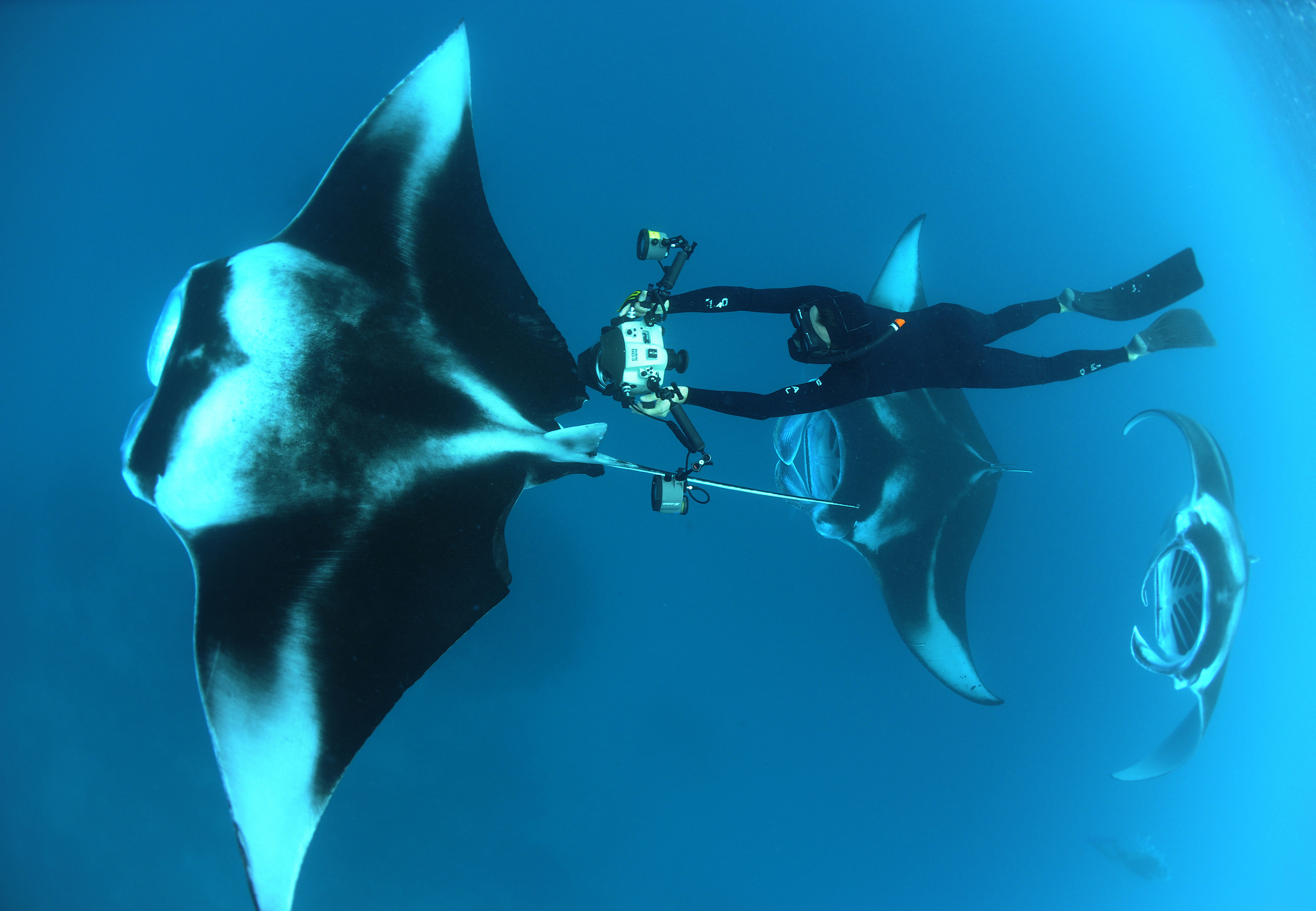

Hands down, it was the 2008 shoot for my National Geographic Magazine story on Manta Rays. I worked with my friend and marine biologist Guy Stevens to document a unique feeding aggregation of manta rays in the Maldives. During the monsoon season currents wash swarms of krill into Hanifaru bay, a cul-de-sac in the reef. This attracts up to 250 manta rays into an area the size of a basketball court. Sometimes it is a highly choreographed ballet of manta rays feeding in an elegant vortex, but it can quickly turn into a train wreck, with rays crashing into each other left, right and center. Though mantas are placid, graceful creatures, they tend to loose coordination in the group feeding context. In short, it is total chaos and getting the images required being right in the middle of all of it. Being knocked unconscious by these giants was not out of the realm of possibilities. However, to the manta rays' credit, I only had one minor collision and a few close calls. This was my first story for National Geographic Magazine and it launched my career as an assignment photographer.

What is the story behind your famous white shark kayak image?

When I began work on a book about white sharks in 2005, I had no idea that this project would yield my most well known image to date. For nearly a year I worked with Michael Scholl and scientists at the White Shark Trust to create novel images of white sharks in South Africa. The team observed large numbers of white sharks venturing into shallow water during the summer months. In order to figure out why, the researchers tracked and observed the sharks’ movements but were regularly thwarted for two reasons. The inshore realm was treacherous, humped by rocky reefs and sandbanks. Secondly, the sharks’ behavior seemed to be affected by the electrical fields from the boat’s engine.

I suggested using a kayak as both a photographic platform and a less obtrusive way to track the sharks. I was met with what I would call cautious enthusiasm. Therefore, I was voted to be the one to test the waters. So there I found myself in a “yum-yum” yellow plastic sea kayak as a 15-foot (4.5m) great white shark approached. However, white sharks are much more cautious and inquisitive than aggressive and unpredictable. And this proved true with our experiment; at no time did the sharks show any aggression toward our little yellow craft.

The story of this particular photograph began on a perfectly calm and glassy sea. I tied myself to the tower of the White Shark Trust research boat and leaned into the void, precariously and patiently hanging over the ocean. The first shark came across the kayak, dove to the seabed, and inspected it from below. I trained my camera on the nebulous shadow as it slowly transformed into the sleek silhouette of a large great white. When the shark’s dorsal fin emerged, I thought I had the shot but hesitated a fraction of a second. In that moment, the research assistant in the kayak, Trey Snow, turned to look behind him, and I took the shot.

I knew the image was iconic, but I could not have predicted the public response. When the photograph was first published many thought the photo was a digital fake. To date there are still several websites that debate its authenticity. Not only is the image real, it was one of the last images I took using slide film before transitioning to digital.